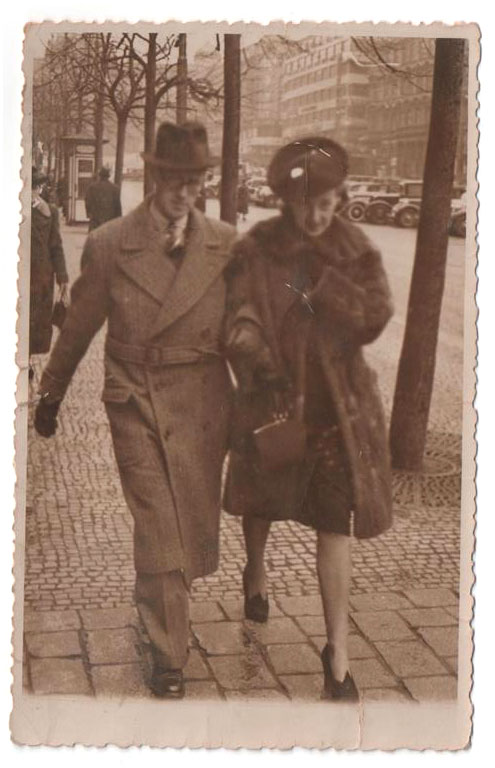

My grandmother ‘Nanan’ was born on 17th May 1914, she would have been 100 today. When going through her files a few years ago my mother found a few sheets of paper containing a typed up account of her experience of being in Prague in 1939 when the Germans arrived, I have reproduced the text in full below. She was 24 at the time. No need to editorialise.

THE GERMAN OCCUPATION OF PRAGUE

The relief at being at last able to put one’s thoughts into words, after having been bottled up in German Territory must be experienced to be understood. We experienced this relief upon our arrival at Basel from Prague, after our seventeen hours’ journey, and after five days in the occupied territory. One learns to appreciate the plight of the refugee, having been in much the same position for a short time.

Our first intimation of the occupation to come was on Tuesday, March 15, when in returning from the office shortly after 7pm we were struck, firstly by the number of people, and secondly by the atmosphere, which seemed electric. The main streets of the town were lined with police and loudspeakers mounted on poles were exhorting the crowds to preserve order. German supporters, very few in number, were provoking the people by wearing the hated white stockings and by waving Nazi emblems. Every now and then a scuffle would take place, ending by forced separation by the police. For the most part the crowds were sullen and they seemed rather dazed. Later in the same evening a parade of Germans took place through the town. They were greeted in silence, or by boo-ing. We were told on that evening in the restaurant that the Germans would soon be in Prague. Our informed, a Czech, said this in a half unbelieving manner, little knowing how right he was to be proved. All night the wireless continued to operate, and people congregated until late in the driving snow to obtain news.

On March 16, at 6am the first German troops crossed into Czecho-Slovakia. The first troops arrived in Prague at just after 9am watched by unbelieving crowds, only after the conviction of the tragedy which had come to them had begun to be appreciated did the Czechs give way to boos and cries of derision. The German troops did not retaliate in any way, and their discipline was remarkable. The principal hotels were immediately commandeered, at least in part, by the German staffs, the accommodation being provided by the forced expulsion of persons already staying in the hotels. Naturally the first people to suffer such expulsion were those who would find it most difficult to get other shelter, the Jews. The hotel ‘Alcron’ became the headquarters of the Gestapo, which was immediately set up, and thus, together with the taking over of the postal services, wireless stations and communications generally, completed the German stranglehold in the city. In what has become the accepted practice in German occupation, a 8pm curfew was imposed on the first night and during the hours of darkness, the Secret Police, armed with lists said to have been prepared long before, made a large number of arrests. It was said that the number of cases of suicide on the first day was eighty, while on the second day so many occurred that no count was taken. An immediate check up of all foreign visitors was taken, we were informed that only in very special circumstances could we leave the town. All telephone calls out of the country were tapped, the clicking on and off of the Exchange being very distinct, and most mail was opened. No newspapers from England were delivered. The ‘Prager Tagblatt’, a Czech paper, printed in German, appeared with the appearance of having been dictated from Berlin, as indeed it probably had, and attempted to tell the Czech people how pleased they were that deliverance had now come. This paper, and in all probability, all other Czech papers, contained no foreign news of any sort, at least up to March 20. The impression the Germans wished to give was that the rest of the world had given the new Protectorate its blessing.

And the feelings of the Czechs? They are a race of proud people, strongly conscious of their ancient ancestry and anxious to uphold it. They are disgusted at the methods employed by the Germans, and further surprised that a great nation should sink so low as to employ such methods. The Germans stated that the Czechs could not preserve order in the country. This was the case only in Slovakia and here it was the opinion in Prague that the disorders could be attributed to Germany. One example of the lengths to which the German ‘arrangements’ in a country will go was told to me by a Czech in Prague. It was that on going home, to an outlying part of the town, he was passing a house connected in some way with the German section of the Prague University. He was surprised to see stones come out of the windows of the building, and on returning about a quarter of an hour later, he saw German students lying on the ground as if dead or injured while their compatriots filmed the incidents, as an incentive to the people of the German Reich to free their oppressed brothers in Czecho-Slovakia. While it is impossible to say that no incidents of any sort took place against the Germans in Slovakia, it can be safely stated that a large number of alleged incidents were staged and a large number were brought by the Germans upon themselves by the deliberate provocation of the Czechs.

March 16, saw the arrival of Herr Hitler and the best weather Prague had seen for a number of days. His arrival was a signal for the German planes to come flying low over the town, making a terrific din, in order to impress the Czechs with their importance, against so strong an enemy. All day the German tanks, armoured cars and lorries paraded the streets, the whole effect being calculated to awe the population. All the time the number of German troops in the town increased, until at the time of our departure a number of 300,000 was said to have been reached. The exchange rate of the Reich Mark to crown had by this time been stabilised at a rate advantageous to the Germans, who were able to buy in Prague things not obtainable in Germany. The Jewish shops were already closed, only stocks being sold. Queues of people were lined in front of all of them, in the hope of picking up bargains. There did not seem to be any outward show of malice towards the Jews, but that may come later.

During this period, when no news was obtainable of the reaction of the outside world, business in Prague was ordered to be carried on as usual. Certain features abhorrent to German Kultur were at once removed, one example being that a film of Elizabeth Bergner could not be shown, as she is a Jewess. No doubt in time Czecho-Slovakia will also be unable to see good foreign films, as the method in Germany it to ban all but second rate foreign productions in order that the home produced article shall appear better in the eyes of the German race.

At this time no one was allowed to leave the city, and it was only after a few days that it was announced that to leave the city we required a permit from the Commander of the German forces in Prague, this requiring personal attendance. The office was immediately besieged by hundreds of refugees. Only a few were allowed to enter at one time, and all were subjected to an examination, the firth question being whether one was Aryan. A negative answer resulted in the non-issue of a pass, whatever the passport of the applicant. After a time we decided that it was no use trying personally to get these passes, and therefore visited the British Consulate, and eventually persuaded the authorities to exercise influence, when the necessary pass was obtained after a wait of about two hours. The relief was unbounded.

The British Legation was housing four newspaper men who had been caught by the suddenness of the German coming, and who had taken refuge there, as they were on the black list of the German Authorities. They were joined by several members of the Refugee Committee, and by some German Socialists, outlawed from their own country. These latter were told by the Legation Authorities that in the event of the German police asking for them, they must go. In such a state of apprehension in the shadow of the concentration camp these unfortunates lived on, up to the time of our departure on March 20. The four journalists were tortured by the thought that the Legation, having no diplomatic grounds for its continued upkeep, would close, leaving them to fend for themselves. One man had already had experience of a German gaol. The refugee committee members were of a different frame of mind. They intended to stay in Prague until they were ejected. The head and prime mover of this movement was an Englishwoman, who worked about 16 hours or more per day. She had refugee women in small hotels in different parts of the town, and was endeavouring to get them over the Polish frontier to safety. Things were of course difficult for her, and were not made easier by the fact that she was continually under observation by the German Authorities. It was she who advised us to cross into Poland with her and the refugees if the situation got any tenser. We decided to risk leaving by way of Nuremburg, safely, as things turned out.

Having obtained the necessary pass on a Sunday, we were forced to wait until the following morning to obtain a visa to travel across Germany to Switzerland. This took some little time, and it was with great relief that we eventually saw the familiar blue of the Wagon Lit, and the label ‘Paris’. West Europe seemed like a distant and higher type of civilisation.

At the German-Czech border a number of refugees were turned out of the train by the secret police – these poor people had in some cases all their worldly possessions with them. They were dumped on the platform, and the people left to fend for themselves. We travelled with an Englishman who had already made the attempt to leave the country on two occasions, and had been twice turned back to Prague. He said that on the second occasion he travelled by road, and that for the whole distance, 80km or about 50 miles he passed German troops marching into Prague.

The journey through Germany was quiet, if rather nerve-wracking. We had no news of the outside world, and half expected war to be declared while we were still in Germany. The feeling of being bottled up continued until we reached Basel. It was most uncomfortable in dining cars to feel the eyes of the Germans staring at one all around, knowing that one was English. The train, an express, seemed painfully slow, averaging as it did about 20 miles an hour. This can be put down to the fact that the track has been allowed to get into bad condition and the want of repairs to the rolling stock. On this journey we had occasion to speak to a German Veteran of the Great War. He had been a waiter in London, and after the war had had work in Nice. He had returned to Germany in 1930 or so, and said that it was the greatest mistake he had ever made. He said that there was no use in Germany for men like himself who had served his country, and as a consequence were not able to work. He was not content with the regime. By contrast, a young German officer in Prague, who had come from Berlin, said that he was a strong supporter of the regime. He thought that the fact that many people were forced to work 14 hours a day, and often on Sunday, was a tribute to the State. He said that the German troops in Prague were driving South East.

It is difficult to say what will be the outcome of the Protectorate. In the opinion of the Czech people only one thing is eventually possible, an they are steadfastly awaiting their opportunity to expel the German rule from their country, confident in their ability to stand for themselves, and certain that their time will come.

What a shame that it was only a few sheets of paper…

Breathtaking….thank you so much for posting this.

Terrific first-hand account. Thanks!

Amazing account. Wish there was more.